"And they did not listen to Moshe, from short spirit and hard work" (7:9). Moshe had a daunting dual task before him. Not only did he need to demonstrate to Pharaoh that he must free his slaves, he needed to convince the Jewish people that they would be better off following him into the desert. And the latter was a prerequisite for the former.

"Even the Israelites will not listen to me; how can I expect Pharaoh to listen to me?" (7:12). Moshe felt inadequate for the formidable challenge that lay ahead. He lacked an important skill for any aspiring leader: the ability to deliver, as we call it today, a good thirty-second sound bite.

It is the rare public leader who is not an eloquent orator. While the message may be more important than the medium, without the medium it is most difficult to ensure that the message is heard. What we say is important, but how we say it is often more so, and Moshe Rabbeinu understood this well. His repeated pleas that he was a poor communicator are the basis for his reluctance to take on the position of redeemer of the Jewish people. Without the gift of persuasive speech, he felt that he was doomed to failure: "I have uncircumcised lips; how will Pharaoh listen to me?" (7:30). And G-d acquiesced immediately thereafter, telling Moshe that "your brother will be your spokesperson" (8:1).

Without Aaron and his gift of eloquence, the redemption would have been stillborn. In the end, Aaron's eloquence did not matter, as Pharaoh's heart was hard as stone; but his presence allowed Moshe to carry out his task. However, convincing Pharaoh was the lesser of the tasks before Moshe.

Man has an amazing ability to adapt to almost any situation. Despite the hardships of slavery, the Jews in Egypt considered it preferable to the unknown of a barren desert. The Jews were forced to work hard, but they had their basic needs provided for them, something that could not always be said of their sojourn in the desert. There was no lack of water in Egypt, and even those who did follow Moshe often yearned to go back. Bringing freedom to those who do not necessarily want it is a most difficult task.

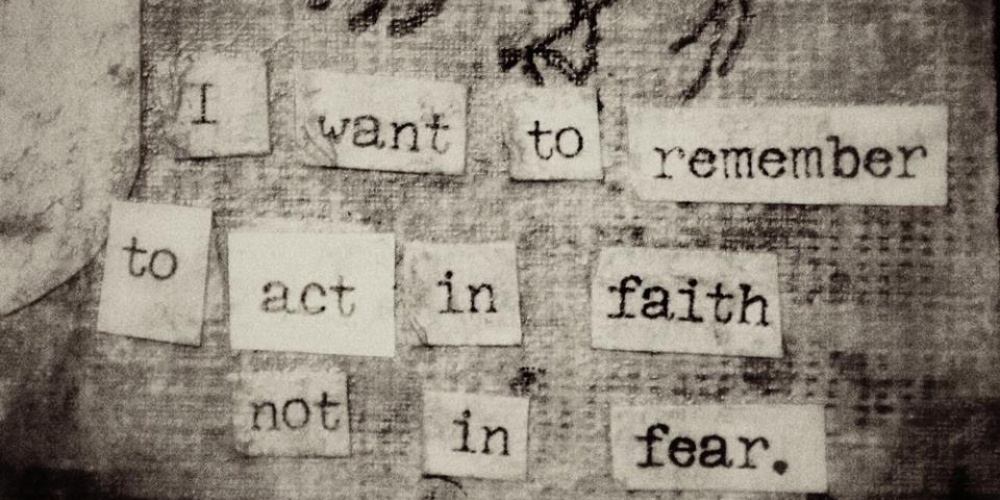

The Jewish people were quite capable of listening to Moshe and his message; capable, but unwilling. They were, as Hizkuni (see 6:9) notes, "afraid" to listen to Moshe. To accept Moshe's message would mean they would have to change from passively accepting their fate to actively shaping it. They could no longer blame their misfortune on others, nor could they claim victimhood for their misery. Their troubles would be of their own making. And this was very scary. It is so much easier to blame others rather than take responsibility oneself! Fear, not of life under a tyrant but of life without one, had paralyzed the Jewish nation. It was this scenario that Moshe was called upon to change, and he felt inadequate to the challenge.

Tragically, it would take ten plagues not only to teach the Egyptians who G-d is, but also to teach the Jews to accept and trust in Him. With the death of the firstborns, an even greater fear gripped the Egyptians as they ordered the Jewish people to leave. The Jews, sensing a historical moment of epic proportions, overcame their love of the status quo, slaughtering the paschal lamb and triumphantly leaving Egypt at midday.

Despite—or perhaps because of—our great freedom, modern man in is often still enslaved and fearful of change. Why rock the boat when it is not sinking? Regardless of the issue under consideration—health habits, family responsibilities, community involvement, Talmud Torah—the fear of change and/or failure that accompanies an attempt to improve is natural. It often takes a major crisis, be it a financial meltdown or a war, for man to gain the courage to (one hopes) march forward. May we march forward with confidence, vigour and purpose as we navigate the challenges before us.