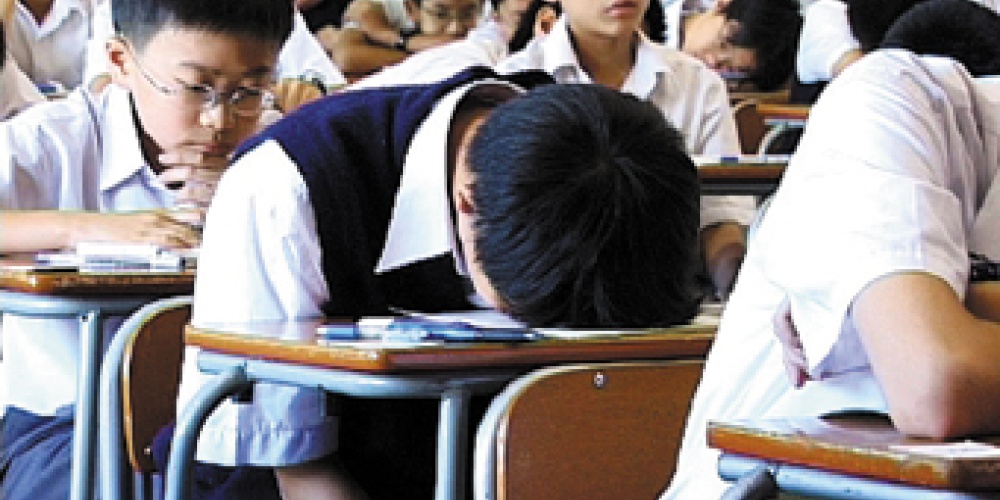

I imagine I am not the only one who has dozed off during a lecture. While I might manage to pick up a point or two, surely such dozing limits my ability to contribute to the discussion at hand. Yet there are some who can sleep and learn at the same time; some whose minds are so full of learning that even when they sleep, they learn.

Reish Lakish taught that dough that was mixed with wine, oil or honey and allowed to leaven would not be considered chametz (Pesachim 35a). The Gemara recounts how "Rav Pappa and Rav Huna the son of Rav Yehoshua were sitting in front of Rav Iddi, the son of Avin" who was "sitting and dozing". Unfazed by this, Rav Huna and Rav Pappa were discussing the reasoning behind Reish Lakish's teaching. Rav Pappa explained that it is based on the verse (that we will read this Shabbat), "do not eat chametz seven days you shall eat lechem oni" (Devarim 16:3). By linking the prohibition of chametz with the mitzvah of matza, the Torah teaches that only that which can be used for matza can become chametz. With the Torah describing chametz as lechem oni, poor man's bread, mixing in wine, oil or honey would convert the matza to bread for the rich, rendering it invalid for the seder--and thus, unable to become chametz.

The above legal ruling has much broader application than law alone. Freedom is only meaningful in the context of slavery. One who has never experienced slavery and suffering, persecution and poverty cannot appreciate freedom and fun, relaxation and riches. Matza is only matza in the context of chametz, as chametz is only so in relation to matza.

The disqualification of such "rich man's matza"--what today, we call egg matza--is such that Rabbeinu Tam, the grandson of Rashi and perhaps the greatest of the Tosafists, used to eat it on erev Pesach for lunch--a time when one is forbidden to eat both chametz and matza. Flour mixed with wine, oil, or honey is neither.

However, the Talmud quotes a contrary ruling; that one who soaks matza in water and swallows it whole would not fulfill the mitzvah of eating matza, this not being a the normal way of eating. Yet, if such soaking caused leavening, one would be liable for eating chametz. Apparently, chametz and matza have independent definitions.

I would have suggested that there is no contradiction. Matza and chametz define each other, in terms of their baking. Eating them, however, is a separate matter--and eating abnormally only means one did not fulfil the mitzvah to eat matza; however, it still retains the status of matza. But that is not what Rav Iddi had to say.

While he may have been dozing, he was also listening closely. He awoke and said to them: "My children, the reasoning behind Reish Lakish is that the matza is made with fruit juices, and fruit juices cannot become chametz".Chametz means flour and water that is allowed to leaven, and nothing else. Whether matza is only flour and water that has not leavened was not the issue at hand. It could very well be that flour mixed with wine, oil, or honey that has not leavened is perfectly fine for matza, a view we find on the following page in the name of the Sages. Such a view would interpret the word oni to mean, "the bread on which many things are said"; i.e., we have the matza before us as we recite the Haggadah and Hallel[1].

While some may marvel at Rav Iddi's sleep patterns, what I find even more remarkable is the fact that Rav Huna and Rav Pappa dared not wake him--despite their assumption that he would miss out on learning. If serious students of Torah are sleeping, it is because they need to, and we must not deprive them of such. This is a concept teachers of Torah would do well to remember. If a student is sleeping in class, it is because he or she is very tired--or, possibly, because the class is boring. If it is the latter, it is the teacher who needs to be "woken up".

[1] This debate is part of a broader debate as to whether we should interpret the Torah based on how it is spelled or how it is pronounced. The spelling in this case is ANI,meaning poor; however, it is pronounced ONI, meaning to answer. By differentiating between kri and ketiv, the oral and the written word, the Torah teaches a dual meaning to matza. It reminds us how the slave could not speak, but as freed Jews, we can and must sing the praises of G-d.