One of the methods used to help people remember those whom they meet is the mnemonic device of associating the person with some easy-to-remember concept. By linking the new with the known, we increase our capacity to retain that new information.

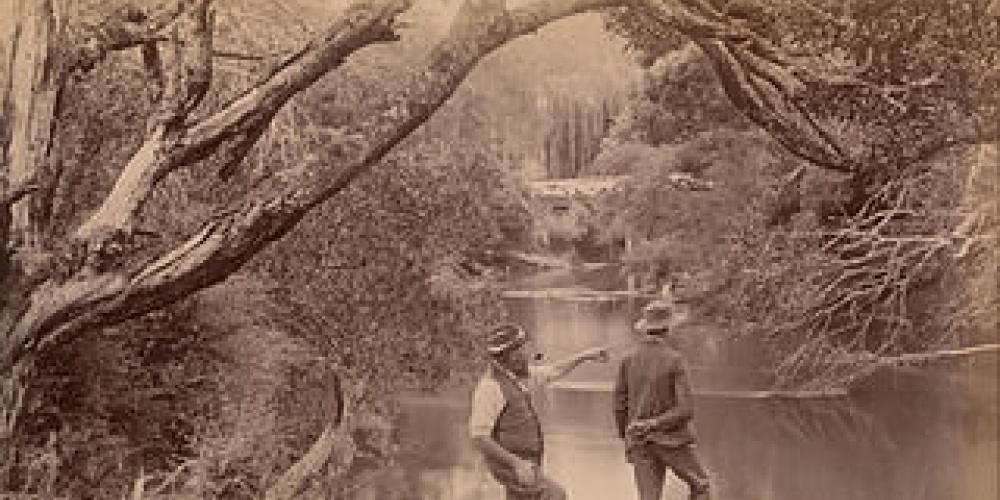

For our Sages, there was no better association than that of Torah. "When Rabbi Abba the son of Shumni and Rav Menashia the son of Yirmiya from Gifti were talking leave of each other on the banks of Yofti River, they said to each other, 'Let us say something that the other has not heard, as Mari the son of Rav Huna said: a person should only depart from his friend with words of Jewish law; as a result of this, he will be remembered'" (Eiruvin 64a).

The example cited by the Gemara is most fascinating. One of the two (the Gemara does not say whether it was Rabbi Abba or Rav Menashia) began by teaching the difference between being under the influence of alcohol,shatui, and being drunk, shikor. This distinction clarifies the immediately preceding Talmudic discussion on the impact of drinking on various aspects of Jewish law. One of those involves prayer, where the Talmud rules that "ashatui should not pray, but if he prays, his prayer is a prayer; a shikor should not pray, but if he prays, his prayer is an abomination". A shatui, he explained, is one who can speak before a king; whereas a shikor has drunk so much that he cannot appear before a king.

When one drinks too much (thank G-d, I have no personal experience!), it is quite common to become forgetful. Alcohol, at least temporarily, alters our perception of reality (making driving so dangerous). By leaving a friend with words of Torah, we try to keep memories alive and associate the finite with the infinite. This same concept is expressed in the custom of learning Torah in observance of a Yahrzeit, linking the living with those no longer part of this world. The imagery of the two rabbis parting with words of Torah on the banks of the river highlights the link between water, the basis of physical life, and Torah, the basis of Jewish life.

Yet, while excessive drinking is frowned upon (to put it mildly), Rav Elazar ben Azaria taught: "I could justify the exemption from judgment of all the world from the day of the destruction of the Temple until the present time, for it is said: 'Therefore hear now this, thou afflicted and drunken but not with wine'" (Isaiah 51:21). Rav Elazar ben Azaria, who personally lived through the destruction of the Temple, understood that in a post-Temple period, no one should be punished for non-observance. The sorrows of the exile have caused our sinning, like a drunk oblivious to his actions. Take away our suffering, Rav Elazar ben Azaria argued, and we will be able to focus on the message of Torah.

Rav Elazar ben Azaria joins a long line of rabbinic attempts to mitigate and explain the wrong choices we so often make. Yet the Talmud unfortunately (or perhaps most fortunately) rejects his analysis. Excuses, even very good ones, are not enough. We may not drink away our sorrows; a drunk is responsible for his actions: "His buying is buying and his selling is selling; if he violates a crime that carries the death penalty, he is put to death...the principle of the matter is that he is like a wise man in all matters except that he is exempt from prayer" (Eiruvin 65a).

While the Gemara rejects Rav Elazar ben Azaria's claims, that was in the second century. Perhaps, after 1,900 years of exile and living in a post-Holocaust age, his arguments resonate with much greater force. The fact that after so much suffering--suffering that Rav Elazar ben Azarai could not envision--Jews still identify as Jews and with Judaism even while engaging in sin is truly amazing, and should exempt us from punishment.

While rejecting his overall argument the Talmud does accept Rav Elazar ben Azaria's teaching in the realm of insincere prayer. Prayer requires the utmost of devotion and clarity, something not possible if one has consumed alcohol[1]. With the destruction of the Temple, and the problems weighing on our minds, we can justify prayer without devotion. While the Talmud's exemption from punishment for lack of prayer is rooted in the suffering of the Jewish people, thank G-d, for many today, there is a different excuse: that of prosperity and good times. Thankfully for many, life is so good that beseeching G-d for our needs is most difficult to do[2].

We may have excuses for the lack of devotion in prayer, and our Sages may be able to help us in heaven; but that is also our loss. Prayer affords us quiet time (at least, that's what it's supposed to do) to reflect on--and to develop in the most intimate of ways--our relationship with G-d. We would do well to remember that.

[1] Anything that weighs on our minds preventing proper devotion, technically exempts one from prayer. The list in theory is long indeed, and these limitations are generally ignored today; otherwise, one might never be in a position to pray. (See Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 101:1).

[2] In classic Jewish fashion, we are thus invoking two contradictory motifs, in this case great suffering, and great prosperity. Such are the efforts we must make for our fellow Jews.