“These are the commandments that G-d has commanded Moshe to the children of Israel on Mount Sinai (Vayikra 27:34).” Though it is the Book of Exodus that we associate with Har Sinai, it is at the end of Vayikra that the Torah actually places us there.

“Joseph died at 110 years; they embalmed him, and he was placed in an aron, casket, in Egypt.” So concludes sefer Breisheet. Joseph, who saved so many lives, is dead; and it would be many years before the Jewish people would escape from Egypt. The word mitzraim comes from the root tzar, narrow; the grand vision of Joseph was replaced by the narrow confines of the life of a slave. And if we go back to the very beginning, the “very good” of creation— the abundance of life—will soon seem like a distant memory as things will soon be very bad, with life replaced by death in the Nile.

As sefer Shemot progresses, we move from the depths of despair to the heights of Sinai, from slavery to freedom, darkness to light. Instead of building cities for Pharaoh, we are busy building a tabernacle to G-d; and instead of working seven days a week, we are to rest on the seventh day.

“The cloud of G-d is upon the Tabernacle by day, and fire will be there by night, before the eyes of all the Jewish people in all their journeys”. So concludes Sefer Shemot.

The Jewish people are still on a journey. Receiving the Torah and building the Tabernacle are not enough. It is in the Book of Vayikra that we put the Torah into practice—in the reverse order to sefer Shemot. We begin with the laws of how to use the Tabernacle, how korbanot can help us get close to G-d. As we move towards the end of the book, it is the laws of social justice that take center stage—laws such as not treating our workers like slaves. The link joining these two spheres, the laws between man and G-d and man and man, is the call to holiness. Only with the implantation of “the majority of the essence of Torah” (see Rashi to Vayikra 19:2) can we be said to be at Har Sinai.

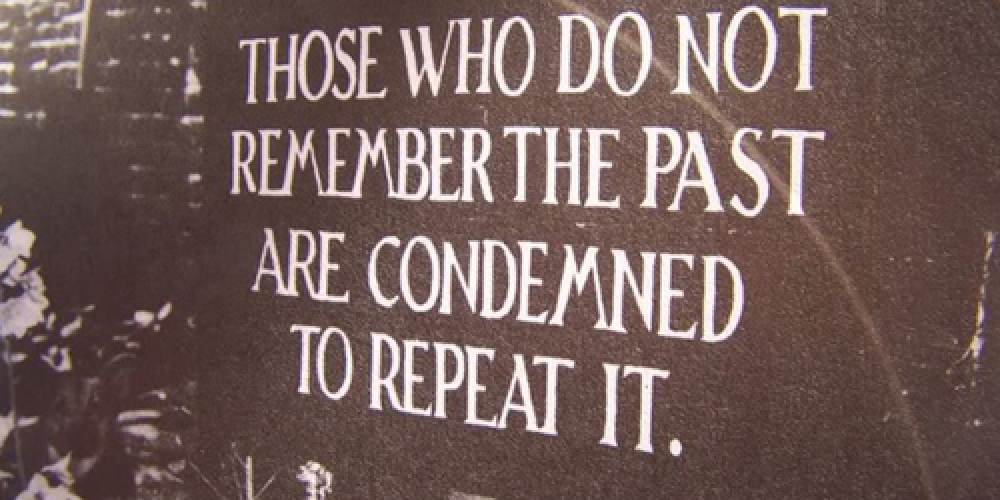

Going through the birth pangs of the creation of a nation, Sinai, a mishkan, and even attaining holiness is still not enough. We must maintain that holiness—a most difficult task. Sefer Bamidbar examines the many instances when we did not. If not us, it would have to be the next generation that would learn from the mistakes of the past. As the book ends, we find a expression similar to the end of Vayikra: “These are the commandments and the laws that G-d has commanded by the hands of Moshe to the children of Israel, on the plains of Moav by the Jordan river, by Jericho.” We can see the goal, but we are not quite there.

Moshe spends almost the entire sefer Devarim exhorting us not to repeat the mistakes of the past. Despite the fact that “no prophet has arisen in Israel like Moshe”(Devarim 34:10), it is time for a new leader to guide us to our destination. We should not be surprised to discover that the last word of the Torah is the word Yisrael. While the other four books of the Chumash end with the description of a physical location, sefer Devarim ends with a description of the people of Israel. If the people of Israel learn the lessons of the Torah, the people of Israel and the destination of Israel will be one and the same.