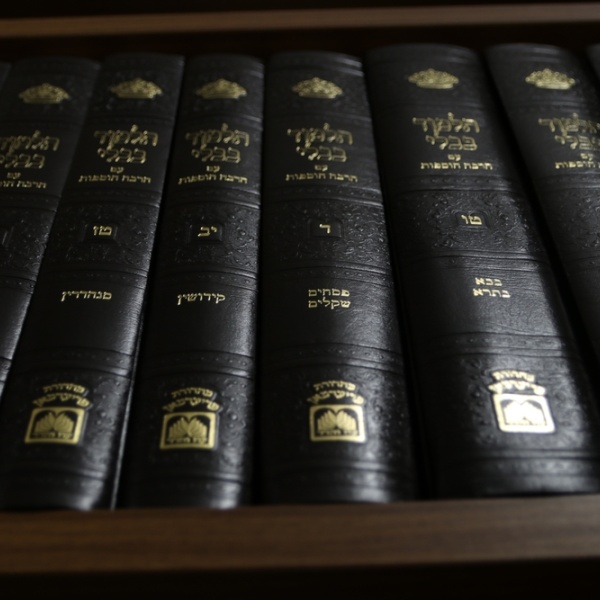

I, probably like many of you began my formal study of Talmud learning Eilu Metziot, the second chapter of masechet Bava Metzia. “These are the lost objects one can keep, and these are the ones that one must declare.” (Bava Metzia 21a) For many years I thought this was a rather poor choice as an introductory Talmud text. It deals with complex and abstract issues more suited to law school than elementary. On the first page we are introduced to what has become one of the more famous Talmudic disputes, that between Abaye and Rava in the case of yeush shelo meda’at.

One of the conditions necessary for one who finds an object to be able to keep it is that of yeush, that the owner give up hope of recovery. Until that happens a finder cannot keep an object. What if one loses an object but is unaware of such when the finder picks it up? Yet had he been aware of such loss, he would have given up hope of recovery; and when he does discover his loss, he has yeush. Abaye and Rava debate whether or not the yeush that he would have had, but did not yet have counts so that the finder can be said to retroactively acquire the object. Of course, this case raises many questions, starting with how a finder of an object is supposed to know if yeush has occurred? How can he know how long the object has been lying there? This is a fascinating debate – and is one of only six places the halacha is in accordance with Abaye in his hundreds of disputes with Rava – but hardly material one would think for an introduction to Talmud.

The reason it was the first pererk I studied is based on historical factors that have little application to Jewish education in the West. Traditionally only the intellectual (and financial) elite studied Talmud, perhaps some 2-3% of the population. Having the masses study Talmud was just not economically feasible. By the age of bar-mitzva most men (the notion of mass Talmud study for woman was inconceivable) had already begun to learn a trade. Fortunate were those who received any formal education in any field beyond bar-mitzva.

But the non-study of Talmud went beyond economics. A person was expected to learn a trade or start a business to provide for his family. Torah observance was learned mimetically with children seeing how their parents practiced our faith. While great honour was given to Torah scholars the general populace was expected to lead pious lives with whatever time could be allowed for study spent on Torah, Mishna or ethical teaching. Whatever Talmud study there was, was limited to Ein Yaakov, a compilation of aggadic or non-legal teaching of the Talmud, mainly stories of our Sages. The notion of kollel study for all was not a goal, even if it could have been made economically feasible

The Talmud itself was written by and for Torah scholars – and likely not intended for the masses. Some of the sharp language and attitudes expressed were meant for scholarly eyes and ears only. Just as lawyers, doctors and other professionals communicate with each other in a language not meant for laymen so too our Sages communicated with each other in a language only one well versed in Talmudic syntax and culture could appreciate[1]. Those who did study Talmud, being the most gifted of the students, were expected to do most of their learning on their own. Shiurim were thus generally delivered on the most difficult of masechtot, generally those found in (parts of) Nashim and Nezikin.

After the war, in their heroic efforts to recreate the learning of the great Eastern European yeshivot, our day schools (something that did not exist in Eastern Europe) and yeshivot taught that which was taught in Europe – despite the fact that the student population was radically changed. The cheder system of Europe was replaced by day schools and a much different type of yeshiva. For the first time in Jewish history all were expected to study Talmud - and for the Modern Orthodox community from the 1970’s onwards that included women. Many of the teachers in schools through the 70’s were refugees from European Yeshivot - or their students - and thus it was Nashim[2] and Nezikin that was the standard curriculum[3].

While in Europe Eilu Metizot made much sense, the masechtot of Moed, easier and more relevant to the day-to-day lives of today’s students seemed to be the way to go. And in fact today many schools today do exactly that.

Yet over time I have come to see great merit in the “traditional” approach. Our introduction to Talmud begins with the important ethical message that not all we may have belongs to us. One learns the intricate details of the mitzva of hashavat aveidah, balancing the efforts one must make to guard the object and locate the original owner vs. the right to take advantage of one’s good fortune and efforts. We must take great care with the property of others. Even if the legal concepts may be technical and complex the moral messages hopefully ring very clear.

At the same time that which is complex need not be difficult. Talmud properly taught is challenging, stimulating, exciting and tremendously relevant. Improperly taught it is boring, archaic, difficult and irrelevant. As the Mishna itself notes “one who wants to gain wisdom should study monetary law for there is no subject of Torah greater than them for they are like an overflowing stream.” (Bava Batra 10:4)

This not only refers to the intellectual depths and logical constructs of monetary law but is a moral statement as well. There is no area of Torah with more mitzvoth than that of monetary law. With man’s insatiable appetite for money we must have mitzvoth at every possible turn. Our Sages (Shabbat 31a) note that the first question the heavenly court will ask us is “were your business dealings done faithfully?” The study of Nezikin, the laws of “damages” in its broadest sense is meant to sensitize us to the great moral obligations placed upon us. Let’s begin with Eilu Metziot.

[1] This at times harsh language is not at all uncommon in rabbinic literature, where some of the greatest rabbis used language that would make our hair stand on edge. They could feel comfortable expressing themselves in such a manner because they knew the limited readership of their comments and the sharpness of tone reflects the seriousness with which the subject matter was treated. Such is inappropriate today, where there is no longer the luxury of private communication.

[2] One of my more memorable high school experiences was going to the Beit Din of Toronto to witness the giving of a get – we were learning masechet Gittin. I vividly recall many of the details and it was a fascinating experience – though one might think of many other hands on experiences that may have been equally interesting.

[3] While ArtScroll has greatly increased Talmud study I believe the ArtScroll phenomenon is the result of Talmud becoming mainstreamed not its cause. As more and more students studied Talmud study aids became more and more necessary including and perhaps especially sources in English. It seems to me ArtScroll’s great influence has been in the adult study of Daf Yomi – and if one wants to ever gain proficiency in Talmud learning, translations (at least initially) is actually more of a hindrance than an aid. Hard work, sweat and figuring out things on one’s own is still the way to go.